The most frequent dialogue-related errors I see when editing manuscripts have to do with how authors tag and punctuate their dialogue. To be more specific:

Authors tend to confuse dialogue tags with common, mouth-related action beats.

This isn’t going to be a post knocking said-bookisms. While I’m a big fan of reducing the number of said-bookisms in our writing (because I think they’re a crutch), alternative tags have a time and a place, and I’d never presume to tell authors to leave them out of their writing entirely. However, I’ve found that a proliferation of said-bookisms within an author’s manuscript often correlates with the improper punctuation of action beats.

To explain what I mean, let me briefly go back to basics:

What’s a dialogue tag?

Dialogue tags are words that:

- Identify the speaker

- (Sometimes) give a clue re: pronunciation or delivery

- Are verbs which must have something to do with the production of speech

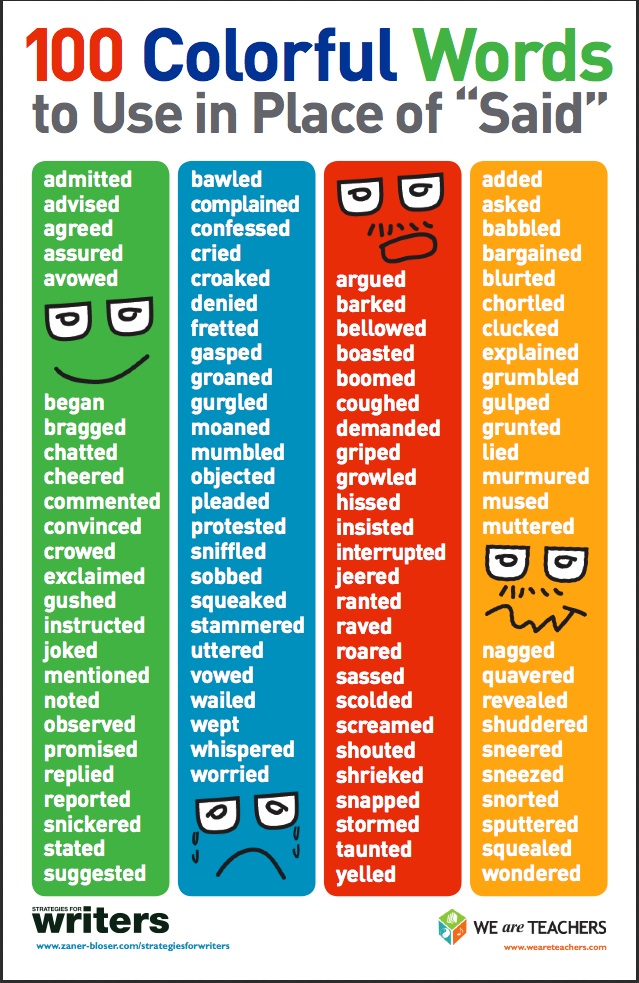

Said and asked are the most common dialogue tags, but said-bookisms like whispered, hissed, or spat are also common in published works.

In fact, here’s a whole list of the most commonly used tags I see in fiction:

- Said

- Asked

- Replied

- Exclaimed

- Shouted

- Muttered

- Whispered

- Yelled

- Mumbled

- Spat

- Cried

- Murmured

- Snarked*

*Why an asterisk for snarked? Stand-by; I’ll get to it in the second half of this post

Notice that all of these words hit bullets 1 & 3; they identify the speaker and have to do with the production of speech. Everything but said/asked/replied also serves as a tone-tag.

Contrast those with action beats.

What’s an action beat?

When referring to dialogue passages, an action beat is a brief physical movement made by the speaking character. Beats are most obvious when they’re short phrases:

- Rubbed the back of [her] neck

- Bit [his] lip

- Folded [their] arms

- Ran fingers through [zer] hair

Action beats have to do with what the speaker is doing while they’re talking, but aren’t related to the production of speech itself. For example:

- Gestured

- Nodded

- Sighed

- Shrugged

- Grimaced

- Smiled

- Grinned

- Smirked

- Sneered

- Huffed**

- Gasped**

- Laughed**

Here’s the tricky part: many of these one-word beats have to do with the head, nose, mouth, breath, or sound one makes before, after, or alongside speech. While they don’t have to do with the production of speech itself, the simultaneity and proximity to speech means they’re commonly confused with or treated as dialogue tags and not action beats.

Why does this matter?

Because dialogue tags and action beats are punctuated differently.

Punctuating dialogue tags vs. action beats

Consider the difference in punctuation between the following examples:

“I don’t think so,” she said.

“I don’t think so.” She smirked.

When using a tag, the dialogue finishes with a comma instead of a period, and the word that follows the end quote isn’t capitalized. When using an action beat, the dialogue finishes with a period, forming a complete sentence, and the word that follows the end quote is capitalized.

Here’s another example:

“Oh, really?” he asked.

“Oh, really?” He grinned.

Or, to make a direct comparison, let’s take a look at correct vs. incorrect examples:

❌ “I don’t think so,” she smirked.

✅ “I don’t think so.” She smirked.

Or

❌ “Oh, really?” he grinned.

✅ “Oh, really?” He grinned.

In other words, while it’s easy to mix up dialogue tags and simple action beats—and it’s arguable that conflation doesn’t matter from a storytelling perspective—this confusion creates a grammatical error which won’t reflect well on the writing. Improper tagging isn’t always a make-it-or-break-it error, especially for action beats that might slip beneath the average reader’s radar, but when it’s so simple to exchange a comma for a period, why chance it?

“But standard tags just don’t have the same meaning!”

I suspect the conflation of tags and beats happens because action beats add flavor and meaning to the dialogue, enriching it in a way a simple tag can’t. This is understandable! However, there are a number of structural workarounds that let us preserve the intention of the beat while adhering to style guides like the Chicago Manual of Style.

(And keeping our copyeditors happy ;))

Let’s get into the nitty-gritty examples!

The rest of this post is patrons-only. I post a craft blog each month over there, using suggestions and questions from folks at the Schooner+ Tiers. We’d love it if you joined us!