Pause.

Rewind.

There are two vitally important things we should recognize when reading a question like this on the bird app:

- By virtue of being on the bird app, the question is snappy to the point it loses its utility. No, of course an author won’t look like an amateur for using a single ‘shouted’ tag in an 80k novel.

- Always/never writing advice is reductive to the point of absurdity.

So, do I ‘agree with this’ statement? Yes. But also no.

Let me explain.

What are said-bookisms?

Said-bookisms are dialogue tags that identify the speaker and, usually, how the speaker delivers their line. Compare this with standard dialogue tags, which exist only to clarify the identity of the speaker.

To define said-bookisms, however, it’s easier to list what they’re not. While there’s some debate about whether only ‘said’ is an acceptable tag, I think the following three tags fall outside the said-bookism category:

said + asked + replied

In other words, said-bookisms are alternatives to the three most common dialogue tags, ‘said’ in particular. Writers often feel pressure to write anything other than said, either because ‘said’ becomes repetitive in the text, or because they’ve made the rounds on writers’ blogs and read somewhere the ‘said is dead’. Thus, they reach for more interesting alternatives to avoid using the same tag over, and over, and over again.

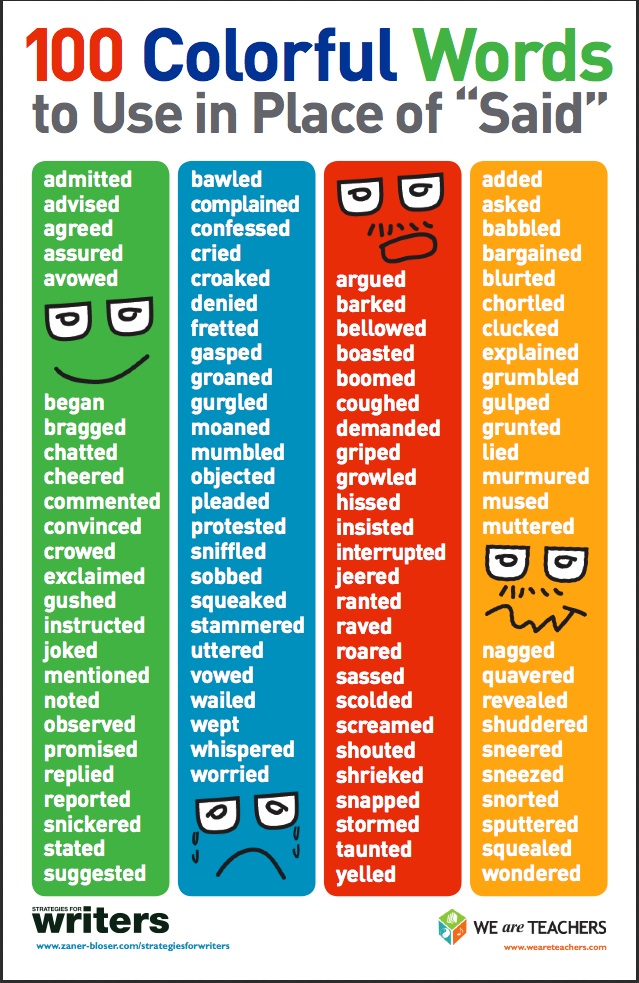

Here are some common examples of said-bookisms:

What’s wrong with said-bookisms?

Many said-bookisms are considered a type of purple prose. When overused, they describe the stage directions in our writing with too much detail or melodrama. Writers who hear that ‘said is dead’ or fear they’re overusing ‘said’ as a dialogue tag tend to lean too much on said-bookisms as a solution. But the truth is, said bookisms don’t solve our dialogue tagging problems. They create different problems.

Let me first add a caveat:

There will be times when a writer will, consciously and intentionally, choose a said-bookism for a particular line of dialogue. This is fine. As with all things, it’s the overuse of said-bookisms that weakens our writing. Too many, and our readers focus more on our tags than our dialogue.

Said-bookisms distract and detract from the prose.

More often than not, said-bookisms detract from the prose instead of adding to it. Words like ‘said/asked/replied’ are invisible cues—they tell the reader who spoke and help the reader keep track of what’s going on without intruding into the story. Said-bookisms, on the other hand, draw the reader’s attention to the author’s word choice. They tell the reader it’s vital they pay attention to how lines of dialogue are delivered—and thus, their inclusion can pull the reader out of the story.

Said-bookisms will always catch a reader’s eye. Thus, their overuse breaks immersion—the ultimate kiss of death for a writer.

But wait, doesn’t using said, said, said break immersion, too?

It can.

“That’s not what I meant,” she said.

“Oh yeah? Then what did you mean?” he asked.

“Now you’re being a jerk. You never trust me,” she said.

“I never trust you? Maybe because you always lie to me,” he said.

^That is objectively terrible dialogue. But the overuse of ‘said’ isn’t the disease; the structure of the dialogue itself is. Changing out ‘said’ for less repetitive words doesn’t cure a structural issue. Instead, it adds a second problem into the mix.

“That’s not what I meant!” she exclaimed.

“Oh yeah? Then what did you mean?” he demanded.

“Now you’re being a jerk. You never trust me,” she cried.

“I never trust you? Maybe because you always lie to me,” he hissed.

While there’s more visual interest to these lines and said-bookisms do give the reader cues re: tone and delivery, this is the equivalent of slapping a colorful band-aid on a gaping flesh wound. It’s distracting, but it won’t stop the bleeding.

If ‘said’ feels dead in our prose, it’s because our prose is the problem.

So when are said-bookisms appropriate?

There are going to be times when we as writers really want to use “shouted/growled/hissed” for stylistic purposes. How do we know when leaning on said-bookisms is appropriate? First, let’s get on the same page by identifying scenarios in which a said-bookism is almost always a poor choice.

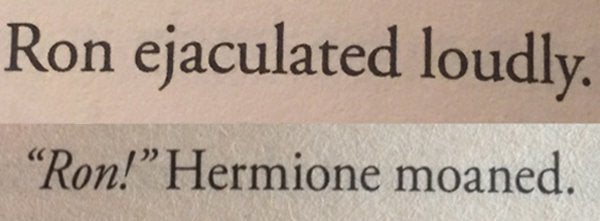

Need I say more?

Look, I’m aware that most writers aren’t quite so egregious offenders and stick with words like “commanded, whispered, spat”. (Most writers also aren’t TERFs who weaponize their massive platforms to further their bigoted ends, either). That said, these two lines of dialogue do a fine job of showing us several Nos of said-bookism use.

For me, inappropriate said-bookism use falls into one of four categories:

The thesaurus

Why use a fancy synonym (ejaculated) when a much simpler one would do? Whenever we’re tempted to pick up a thesaurus for a better way to say ‘said/asked/replied’, we ought to ask ourselves why.

Do we feel the need to Elevate Our Prose? This isn’t the way to do it—not when the end result is confusing, or when the full meaning of the word doesn’t quite fit the situation. Worse still, nothing pulls the reader out of the narrative quite like ‘ejaculated’.

Are we concerned about overusing simpler dialogue tags? Remember, dialogue problems require structural solutions (we’ll get to them)—not a double-down with an out-there tag.

Adverbial tags

JKR used an adverbial tag with “ejaculated loudly,” which… no.

But let’s say she didn’t reach for the thesaurus and used a much more reasonable adverbial tag like “said loudly.” Why not show the reader how the line is delivered instead of telling them? Ron can slam a door, pound his fist on the table, stand bolt upright with jaw agape.

While I don’t think we should strike all adverbs from our writing, their use should raise a yellow flag for our editorial brains. Did we use the adverb where a stronger verb would do? If so, let’s make the switch.

Just… don’t switch it to ‘ejaculate,’ please.

That word. It does not mean what you think it means.

Here’s the thing about said-bookisms: verbs tend to have secondary meanings or colloquial usage that will confuse readers.

“Ron,” Hermione moaned.

…interesting choice.

As readers, we logically know JKR meant ‘complained,’ which she’d use far more commonly than an American English speaker. That said, words like moan, groan, and ejaculate have unintended consequences when used for dialogue tags. Unless the situation and delivery are ultra-clear, they do nothing but muddy our prose.

Remember: a dialogue tag’s primary purpose is to add clarity. Some said-bookisms do anything but.

How is that even possible?

One of the biggest editorial complaints about said-bookisms lies in their physical impossibility. This includes common tags like ‘wept, fumed, smiled’ and more inventive ones like ‘husked’.

What’s wrong with those?

How do you weep words? How do you fume them? What is this, a séance?

You can’t smile words, either, though you can smile while speaking. And holy wow, don’t get me started on husked. What are we, shucking corn for the clam bake? No.

If our characters perform these actions while speaking, that’s fine. Including them in our prose is great, even! But we must do so with action tags, not dialogue tags. An example:

No

- “You look more and more like your mother every day,” her father smiled.

Yes

- “You look more and more like your mother every day.” Her father smiled.

- “You look more and more like your mother every day,” her father said, smiling.

See the difference? Remember: a dialogue tag’s purpose is to clarify the speaker—not to tell the reader what the speaker is doing while delivering that line of dialogue. Those tags must be kept separate.

Despite this, the ‘said-is-dead’ community lives on.

At this point, I hope we’ve established that new writers ought to treat said-bookisms like adverbs. They’re crutch words that prevent us from developing our prose to a higher level, which is why the writing community cautions beginners to avoid them until they’re more comfortable tagging dialogue.

I’ve also seen editors bat statistics around and claim said-bookisms and other non-standard dialogue tags should account for less than 20% of all tags. (Read: tags, not dialogue as a whole.) Granted, if you quote that rule of thumb on the internet, someone will hop into your mentions to inform you that “YOU MUST HATE F. SCOTT FITZGERALD, THEN” to which I’d like to make the following point:

- Literary conventions change with time. This is one of the conventions that has changed. There are many incredible classics that wouldn’t be published today because of stylistic change over time, and that’s okay. We’ve been there. We’ve done that. Time to move on.

Authors of the past, present, and future can, have, and will overuse said-bookisms. That doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

While preparing to write this blog post, I also encountered a twitter comment thread that started: “BUT MY SIXTH-GRADE TEACHER SAID—”

Yes, I’m sure their sixth-grade teacher did. But their teacher aimed to help a middle-schooler write within the conventions of the genre and age category they read at the time. Middle Grade, YA, and Adult fiction all have different stylistic standards. Ditto Romance and Literary Fiction. Said-bookisms are way, way more tolerated in MG than Adult SFF. As writers, we must know our audience.

My least-favorite argument in favor of said-bookism usage is: “BUT I JUST READ AN ADULT ROMANCE ON AMAZON LAST YEAR THAT—”

Was the book self-published, or trad-published?

I’m a banner-waving, card-carrying fan of self-publishing, but let’s not call a spade anything but a spade: self-publishing is expensive, and many authors skip stages of editing that trad-published books always go through. Sometimes, skipping editing comes around to bite them—but not always. An author who hits the market with a fabulous idea at just the right time can do well in self-publishing without professional copy or line editing.

Some authors are pretty darn good at proofing their own work, so this doesn’t necessarily mean the aforementioned Adult Romance was littered with errors. However, I think it’s safe to say that said-bookisms are only ‘making a stylistic comeback’ in spheres where books aren’t required to go through rigorous rounds of edits before showing up for public consumption.

Alternatives to said-bookisms

Whenever a segment of dialogue gives me trouble, I break down my potential ‘fixes’ into four different options. These are structural options at their heart, and being able to flip between them with facility gives dialogue the depth, breadth, and contributes to the veneer of realism we chase with our writing.

Why do I think in terms of structural options instead of rules? As I mentioned earlier in this post, there are few hard-and-fast rules in tagging dialogue, and even fewer “this always works” or “this never works”.

(Aside from ‘ejaculate’. For the love of god, let’s stop using ‘ejaculate’.)

Redundant tags and crutch words in dialogue are structural issues—thus, I try to think in terms of structural solutions when I’m writing. The standard advice when issues crop up is to leave dialogue untagged. Sometimes, simplicity is the way to go! Yet for me, a white-room-syndrome writer, untagged dialogue isn’t always the answer.

Let’s say our character has stormed across the room, positively seething, to ask the POV character, “did you just call me a liar?”

Here are four ways to structure this line of dialogue:

- “Did you just call me a liar?”

- No tag. Context already implies the identity of the speaker.

- “Did you just call me a liar?” he asked.

- Simple dialogue tag identifies the speaker.

- “Did you just call me a liar?” he demanded.

- Said-bookism, but not an outlandish one. It identifies the speaker and how the line was delivered.

- A vein pulsed in his temple. “Did you just call me a liar?”

- Action tag replaces a dialogue tag to identify the speaker, provide information on the delivery of the line, and give a visual cue.

Depending on the lines preceding and following the dialogue, some of these options are better than others. In this case, I’d actually say the standard dialogue tag of ‘asked’ is the weakest given the character’s emotional state. Now, if he were miffed rather than truly raging, ‘asked’ would work better than ‘demanded’. In this case, however, ‘demanded’ is fine—providing said-bookisms aren’t overpowering the rest of the scene.

The other options—no tag, action tag—are also strong candidates. Which of the four we pick, however, is all about context. What does the POV character see? What is the speaking character trying to express? What do we want to communicate to the reader? What do we absolutely need to communicate to the reader?

Depending on the beats surrounding the dialogue, the action tag might prove unnecessary. Or, perhaps there aren’t enough action tags/descriptions in the surrounding lines, and “A vein pulsed in his temple” brings visual interest to an otherwise sparse scene. Here lies the structural fix to the repetitive use of said—and a far more nuanced one than simply replacing ‘said’ with more colorful verbs, or striking every single said-bookism from our writing.

Said is not dead

In conclusion, no, said isn’t dead. Yet deviating from the standard tags ‘said, asked, replied’ won’t necessarily stamp our work as amateur. As with all things fiction writing, balance is paramount.

Do our word choices suit the needs of the story? That is the question we must ask when tagging our dialogue. Anything else simply feeds into a sensationalist social media cycle meant not to stimulate nuanced discussion, but to garner likes and retweets.

How do you tag your dialogue? Do you think ‘said is dead’? Let me know in the comments!

What Would Your Character Do?

What Would Your Character Do? The Inside/Outside Trick

The Inside/Outside Trick Writing Resolutions

Writing Resolutions

Leave a Reply