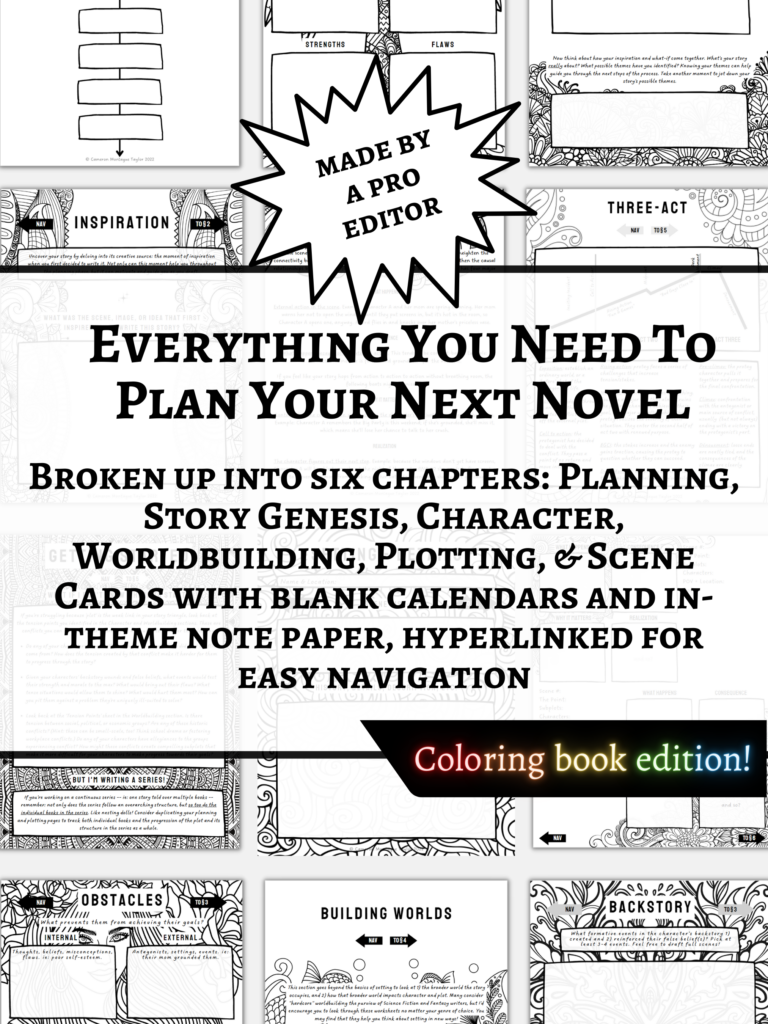

The new, coloring book skin for the digital novel planner is here!

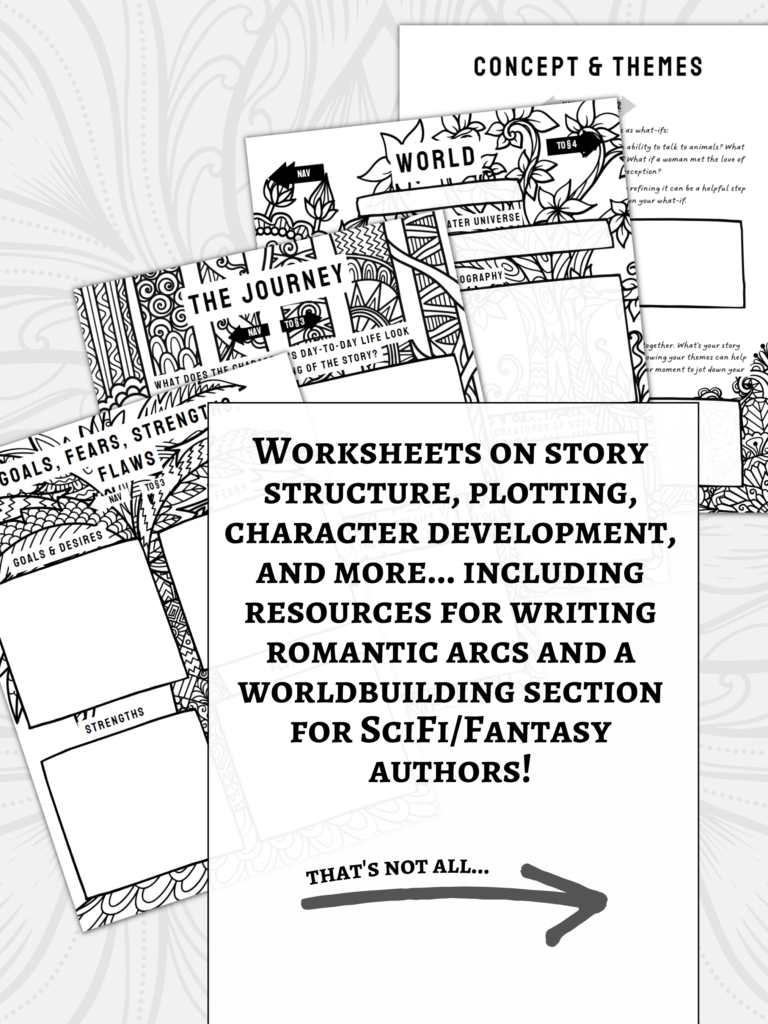

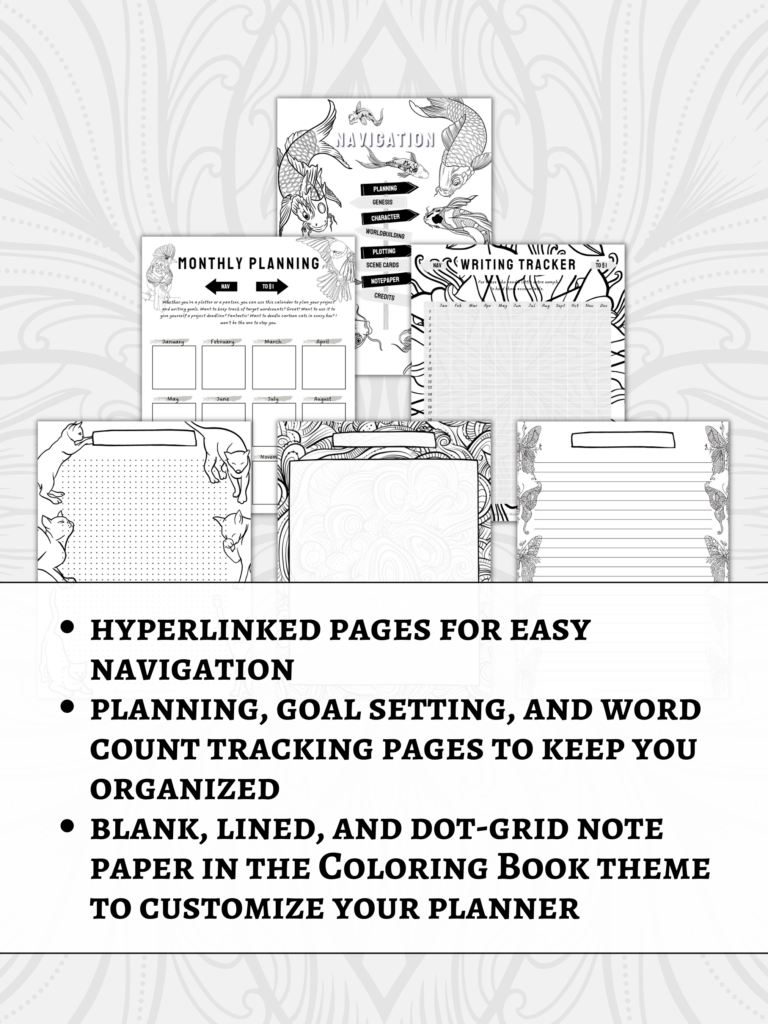

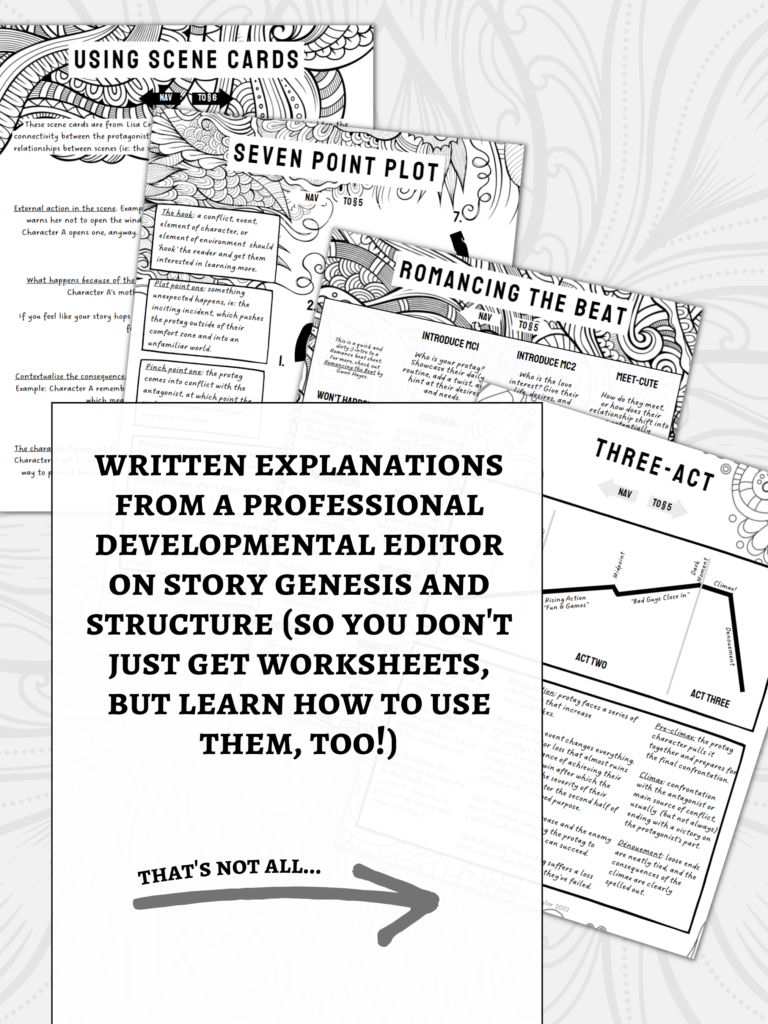

The WIP Novel Planner is a digital (and printable) planning guide for novelists. I’ve been working on different permutations of the planner since last last year, and am very happy with the outcome! So far, folks have really seemed to enjoy using it for the novel-planning process. I’m looking forward to creating new skins in the future, but for now, I intend to turn my focus to craft of writing booklets, so stay tuned for an announcement about that in the near future!

If you’re looking for the planner, you can learn more about it here in my shop. Otherwise, the planner is up for purchase on Etsy and Ko-fi: