By this point, everyone and their cat has heard the world’s most popular piece of writing advice: “show, don’t tell.” It’s a snappy, cute little phrase that feels accurate while remaining frustratingly vague. Though it’s one fiction writing’s most important tenets, I don’t like repeating it verbatim for one big reason:

It’s not a single piece of actionable advice.

“Show, don’t tell” is an umbrella under which a wild number of craft concepts sit. It impacts almost every single aspect of writing prose, and the best method I have to explain it is a metaphor: if your prose is a camera and you’re the photographer, make sure you use the right zoom lens for each scene.

Some parts of the story require a wide-angle. Or a telephoto. Or a macro lens. Showing vs. telling is the act of zooming in or zooming out to focus (or not focus) the reader’s attention on immersive, real-time detail.

This ought not be interpreted literally, either, for setting detail is only one part of the “Show, don’t tell” picture. It impacts all axes of prose in our writing, and in today’s blog post, we’ll be looking at how “show, don’t tell” impacts narrative voice and psychic distance.

Show, don’t tell & psychic distance

First, let’s get clear on the camera metaphor:

Showing means zooming all the way in to focus the reader on vivid details, and telling means zooming out to deliver a broader picture. Therefore, showing brings the reader closer to a character’s consciousness, while telling increases the psychic distance (there’s that word!) between the reader and the character, letting them observe story events from further away.

Like any good zoom lens, our narrative ‘camera’ has more than two binary settings, and as writers, we can choose how far we ‘zoom in’ in order to best suit our narrative.

Certain POVs, like true and subjective omniscient, put a great deal of distance between the reader and the character, often by using a third-party narrator. And while omniscient narrators can dip into characters’ heads, they do so at a distance, observing but not experiencing those thoughts and feelings.

Contrast that with POVs like third limited close and first person, which allow the reader to experience the narrative as if they were the character in question. These POVs often get called “voicey,” because the narration sounds is delivered by the character, and sounds like the character’s spoken voice. Think about Catcher in the Rye, when Holden Caulfield calls other characters “phonies” in narration.

Is one method better than the other?

Arguably, no. Third limited and first person are more popular right now, especially in middle grade and young adult categories, but there are bestselling writers who masterfully use omniscient and somehow still attach us deeply to the characters (think Fredrick Backman). Like any zoom lens, psychic distance is a tool and a choice we can use as writers in order to effectively tell our stories.

So what do these different ‘zoom settings’ look like?

Five levels of psychic distance

First, a caveat: there aren’t five levels of psychic distance.

Or, at least, there’s no dividing line between each of these so-called ‘levels.’ I use five, here, because that was how I initially learned about psychic distance in fiction, and because I think it’s 1) enough to provide nuance without 2) being overwhelming.

For these purposes, think of the levels like this:

- Omniscient

- Omniscient or distant third

- (Close) omniscient or third limited

- Third limited close or distant first person

- Third limited close or first person

Notice how there’s a lot of overlap between them? This is important! It means that, while choosing our POV will inherently limit how close or far we can ‘zoom’ while writing, our narrative camera still comes equipped with a zoom function.

Let’s first take a look at our five levels, then examine why we might choose to zoom in and out between them.

*Note! These examples aren’t meant to be exact rewrites of the same sentence—they’re illustrations of what close vs. distant narration looks like with one character in one scenario.

- Omnicient: furthest from the POV character

It was an unusually warm fall in Tarrytown. On one of the city’s many tree-lined streets, a brownstone door opened, and a woman stepped out onto the sidewalk.

In this example, it’s clear the character (a woman) isn’t narrating the story; she couldn’t have seen the brownstone door open from the street if she’s the one opening it, right?

- Omniscient or distant third: far from the character, but skimming their thoughts

Ida Marie didn’t appreciate the unreasonably warm weather, and feared it would ruin her afternoon walk.

This example is slightly closer than #1. A writer using subjective omniscient might even piggyback these first two examples off of one another, ‘zooming in’ to the character to give us her name and a hint of her mental/emotional state.

This could also be an example of distant third limited, because it’s settled firmly upon Ida Marie’s shoulders. Yet while the reader can skim Ida Marie’s thoughts, this POV isn’t immersive; the use of filtering phrases like didn’t appreciate and feared serve as ‘tells.’ Rather than showing the reader what Ida Marie experiences as she begins her walk, the narrative zooms out to tell the reader what she’s thinking and how she’s feeling. Contrast these telling words with the following examples:

- (Closer) omniscient or third limited—slipping into the character’s body

Ida cursed November’s unreasonable heat, which made her shirt stick to her back as she walked.

Much closer! While this breaks no laws of omniscient (it’s still tell-y), the sensory detail of the shirt sticking to the back brings the reader closer to Ida Marie. This is the true point of crossover between the deepest possible omniscient perspectives and the ‘standard zoom’ of third limited.

- Third limited close, or distant first person—slipping into the character’s thoughts

God, how she hated those second summers. They made her tacky with sweat, shirt turning clammy and gross against her skin.

Here, we’re experiencing Ida Marie’s thoughts along with her, learning that she calls the unseasonably warm parts of fall ‘second summer,’ that her shirt is tacky, that she thinks it feels ‘gross’ against her skin. While this is phrased in third person, it would work in first, too, without coming off as weak writing: God, how I hated those second summers. They made me tacky with sweat, shirt turning gross against my skin.

Some narrative distance remains, because Ida Marie is still telling us how she feels with “she hated those second summers.” Yet although the camera isn’t zoomed all the way in, her voice sneaks in makes an appearance—how she sounds both in dialogue and in her own head—which means this cannot be an omniscient narrator; Ida Marie is now the one telling us the story.

- Third person limited close or first person—deep POV, macro zoom

Another damn seventy-degree day in November. Forget pumpkin spice; this year was sweaty tee shirts, soggy pits, and lungs that ached with every stupid, humid breath.

See the difference?

In this excerpt, we are Ida Marie. We’re so close in her head that we can hear the quality of her voice as if she’s chatting in our ear. This is deep interiority, the last step before pure stream of consciousness. Did you notice how there were no pronouns in the excerpt? That’s not an accident! How often do we refer to ourselves in our own heads? Infrequently, right? Our focus is usually directed elsewhere.

That’s not to say pronouns won’t appear in deep POV (we need them to describe physical action), but they’ll become less common throughout moments of interiority. The ‘macro’ zoom setting on psychic distance gets us so close to the character that we no longer ‘see’ them; instead, we gain an understanding of who the character is by observing their reflection in the world around them. This is the bread-and-butter spot for first person and third limited deep.

How do we decide when to zoom in/out?

There are a variety of reasons why an author might choose to zoom in or out within the boundaries of the POV they’ve chosen. Here are the three that I believe are the most important to consider while we’re writing:

- Voice when writing first or third POV

The narrower the psychic distance, the stronger the POV character’s voice will be in narration, and the more the character begins to feel like a real person. Strong character voice can provide a hook and a handhold for readers to become invested in them and the story they’re trying to tell. Zoom in!

- Managing the reader’s connection and comfort

Though a narrower psychic distance gap is often pushed as a method of strengthening reader connection, there are times when it’s more appropriate to pull back and leave a gap between the reader and the POV character. Authors do so when sitting too deeply in the POV character’s head is uncomfortable and disturbing. This might be the case, for example, when a murder mystery slips into a serial killer’s POV, or when a character commits an atrocity that the author doesn’t want to excuse, sexualize, or romanticize. Zoom out!

- Show, don’t tell

Larger gaps can work better for technical reasons, too. There will be times when the POV character must transmit information to the reader that, while important to understanding the flow of the story, isn’t itself vital to describe in detail, like a time skip or a scene transition. Writers might zoom out to prevent these scenes from bogging down the story, then zoom in when they want the reader to experience a scene alongside the character: clue discoveries, major reveals, battles, sex scenes, love confessions, etc.

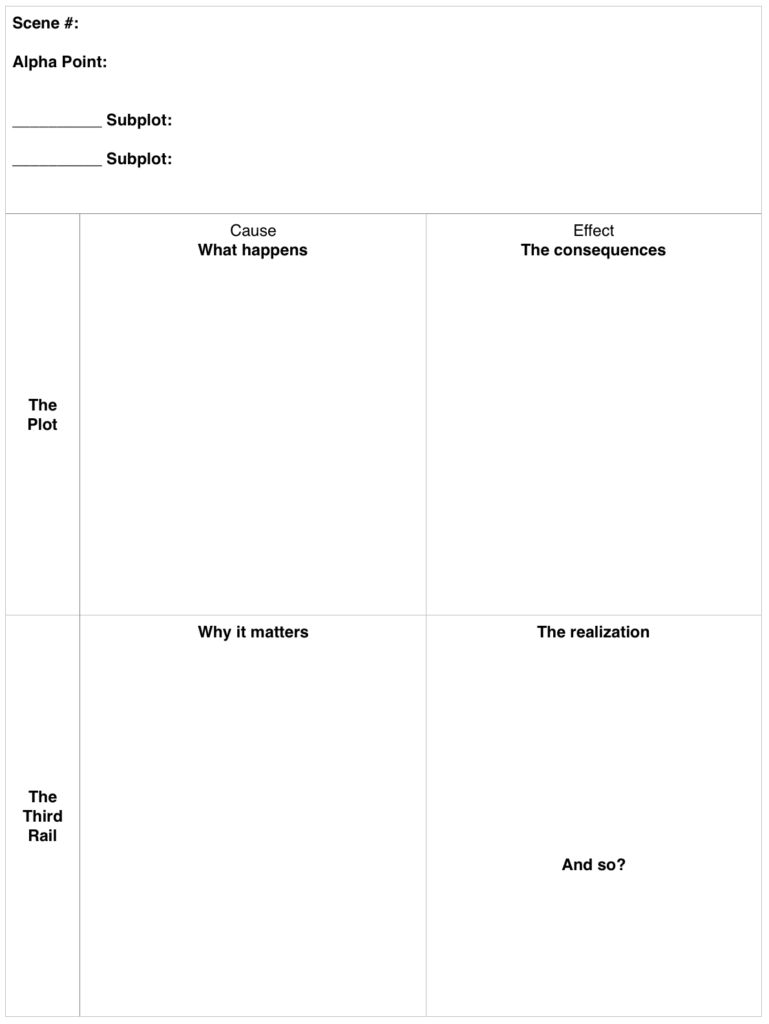

Want to learn more about when it’s appropriate to ‘show’ and when it’s better to ‘tell?’ Check out this infographic.

There’s more to “show, don’t tell”

While there’s more to “show, don’t tell,” mastering psychic distance is a major step towards learning how to strike the right balance in your writing.

Have questions about what you’ve read in the blog post, or more questions about “show, don’t tell” that weren’t answered here? Let’s chat in the comments!

Support the blog

Did you find this blog helpful? Consider becoming a patron to support Cee’s writing!