As a freelance editor, I don’t have a manuscript wishlist in the traditional sense, so in order to give you a better idea of what stories I love (and what stories aren’t a hit for me), I’ve filled out a little bookish survey below. Hopefully, that’ll help you gauge whether I’m the right editor for you and your story.

First, a little intro:

Genres:

- Fantasy and Science Fiction

- Most subgenres

- Horror (cosmic/atmospheric)

- Note: I don’t love vampires, so if they’re your MC or LI, I might not be a good fit

- Cozy Mystery

- Historical Fiction

- (Note: I’m not as interested in 20-21st century settings unless they have speculative elements)

- Dual-genre Romance

- (SFF, Historical, Paranormal, etc.)

Not a Good Fit For:

- Middle-grade or Lower-YA

- Nonfiction, Screenplays, Short Stories, Poetry

- Literary Fiction, Religious Fiction, Procedural/Slasher/Serial Killer

- Erotica or very spicy erotic romance

- On-page sexual assault, dubiously consensual sex, or extreme domestic violence

- Any writing created or modified by an AI reinforcement learning or natural language processing system, such as Chat-GPT.

There are a few areas I specialize in:

Specialties:

- Novels, novellas, series

- Give me your chonky epics!

- Adult and Upper-YA

- LGBTQIA+ characters and themes

- Can sensitivity read for bi and ace rep

- Nautical themes

- Can fact-check for sailboats and scuba diving

Now, onward to the fun part!

The book I’ll recommend to anyone who will listen:

- Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse

Phenomenal epic fantasy. I’m auto-buying the sequels as they come out, but waiting until I have them all to binge-read the rest of the series.

A book I struggled to get through:

- ACOTAR & ACOMAF by Sarah J. Maas

I pushed through the first book for a buddy-read with a friend, then threw in the towel after ACOMAF. It’s not for me!

A book I still think about years after I read it:

- Tigana by Guy Gavriel Kay

The ending. THE ENDING. This book lives rent-free in my head for a hundred thousand reasons, but omg the ending.

A book that let me down in the end:

- The Priory of the Orange Tree by Samantha Shannon

The structure of the last third of this book took it from a 4.5 star read to a 3 star read. I was so immersed in the world and excited for the final battle, but the ending felt rushed/too easy to me — particularly from a fantasy-politics standpoint. That said, I’m still planning to check out A Day of Fallen Night; landing the plane on something so chonky is hard as heck, and I enjoyed the first half of the book enough that I’d absolutely read more Shannon.

The book that made me want to write:

- The Dragonbone Chair by Tad Williams

I’ll admit there’s nothing particularly out of this world about the trilogy, but it happened to be my very first exposure to adult epic fantasy, and ten-year-old me was mind-blown. (Ten-year-old me also wrote the world’s worst fantasy novel immediately afterward, and I’m still obsessed with the genre decades later).

A book I DNF’d:

- Fourth Wing by Rebecca Yarros

Anything that sits in the Maas-Yarros Venn Diagram is probably a DNF for me based on premise, tropes, worldbuilding, and execution. I have absolutely nothing bad to say about folks who enjoy those books — they’re just not for me, and if your writing comps them, I might not be the best fit for your work.

A series I DNF’d after finishing book one:

- The Poppy War by R.F. Kuang

I’m a Kuang fan, but her first trilogy didn’t do it for me, even though I mostly enjoyed (and found a lot of good morsels in) book one.

Three auto-buy authors I haven’t mentioned yet:

- N.K. Jemisin, C.L. Polk, and Fonda Lee

They are all incredible. Need I say more?

If I could experience any story again for the first time:

- The Lord of the Rings

This is a very basic Fantasy-lover answer, and I know adult-me would struggle with the prose, but hooboy what I’d give to experience that feeling of wonder again.

My go-to reads outside the SFF genres:

- Anything by Tal Bauer, Casey McQuiston, or Fredrik Backman

More fun facts:

Other media I love: Good Omens, Star Trek, Our Flag Means Death, Stargate, Supernatural, Dungeons & Dragons (yes, Baldur’s Gate 3), Master and Commander, Pirates of the Caribbean, Zorro, Black Sails, Dr. Who, Marvel Movies (can’t help myself), Firefly, I could go on for days but will restrain myself.

Favorite tropes: forbidden romance, friends/teammates-to-lovers, slow-burns, found family, forbidden magic, magic that comes with a price, political machinations, the only things scarier than the Dark Lord are his human minions, misinterpreted prophesies. This isn’t an exhaustive list of things I enjoy (ie: I love me a good forced proximity or fish-out-of-water story, too), but the aforementioned tropes are my personal crack.

Least favorite tropes: I’m not interested in fated mates*, instalove, instattraction, orphan-is-the-chosen-one, love triangles, omegaverse, and evil without motive / evil for evil’s sake.

*One notable exception: if you’re writing LGBTQ+ fated mates in a queer-inclusive world, I’m down.

A non-exhaustive list of stuff I LOVE to read: Queer-normative worlds, SFF narratives that deconstruct colonialism, epic love stories, diverse casts, interesting magic systems, competent characters being badasses, epic friendships (we love platonic love in this house), dystopias with incisive commentary on the world we live in, cozies, cosmic horror, fairytale retellings, magical quests, historical fantasy, epic SFF with sweeping worldbuilding, space opera, cyberpunk/steampunk/all the punks, portal fantasies with a twist, pirate and nautical stories, all the cool fantasy creatures (will never get tired of dragons and sea monsters), anything that makes me feel like I’m crew on the Enterprise. Again, this is a non-exhaustive list, but I hope this gives you an idea of the *vibes* I love most.

Stuff I just don’t want to read: Fridging, bury-your-gays, on-page sexual assault, gratuitous domestic violence, sexual assault or the threat of sexual assault used as a plot device, romanticized abuse (I’m looking at you, Edward Cullen), romanticized toxic relationship dynamics (I’m looking at you, possessive alpha love interests), white savior narratives, worlds with baked-in misogyny that never gets explored or unpacked, queerphobia.

Something you should know: If you have written a story in which sexual assault is a present or persistent theme, I will put it under the highest-power narrative microscope I’m capable of wielding. I am very, very, very tired of sexual assault being used as a plot device, being used to characterize antagonists and love interests, or being used for dramatic effect without any story- or character-level repercussions. I won’t give even a smidgen of grace or creative license on this point. If reading this makes you nervous, it could be that I’m not the right editor for you.

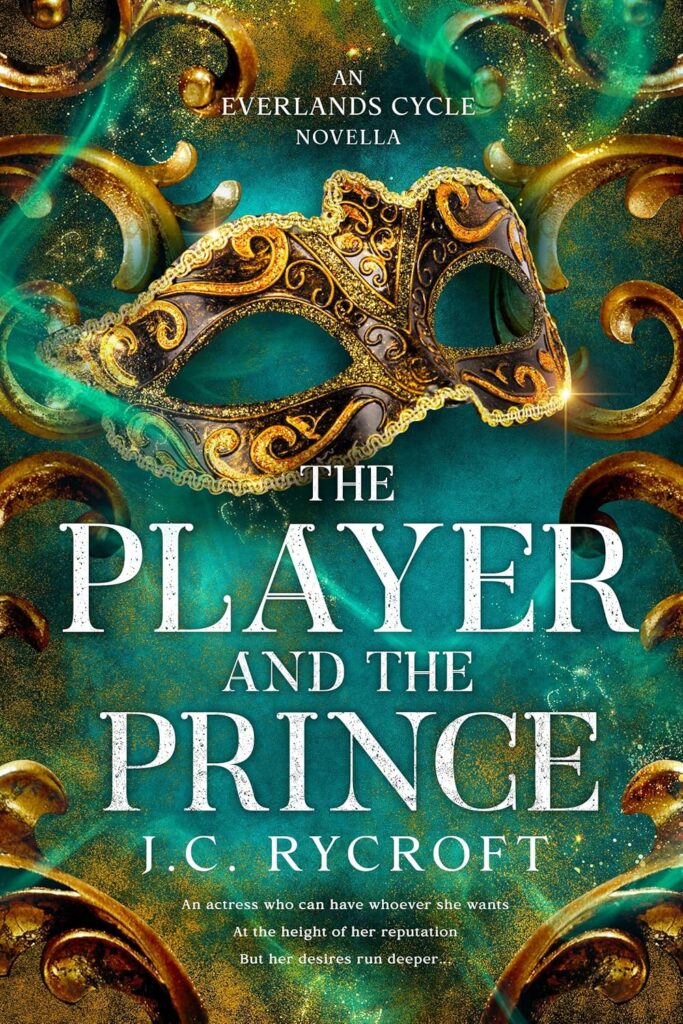

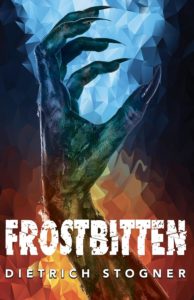

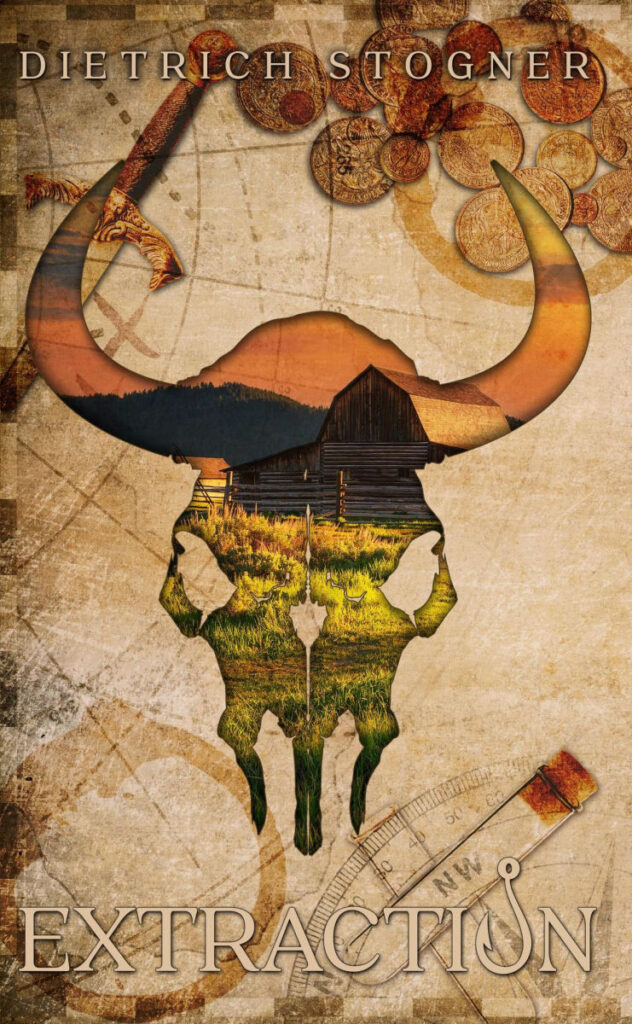

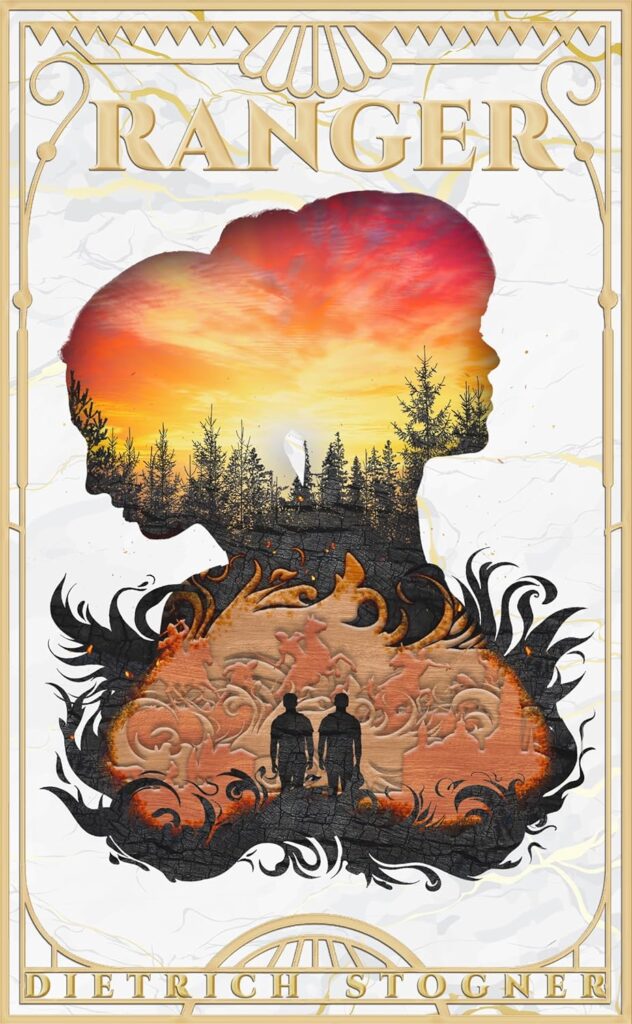

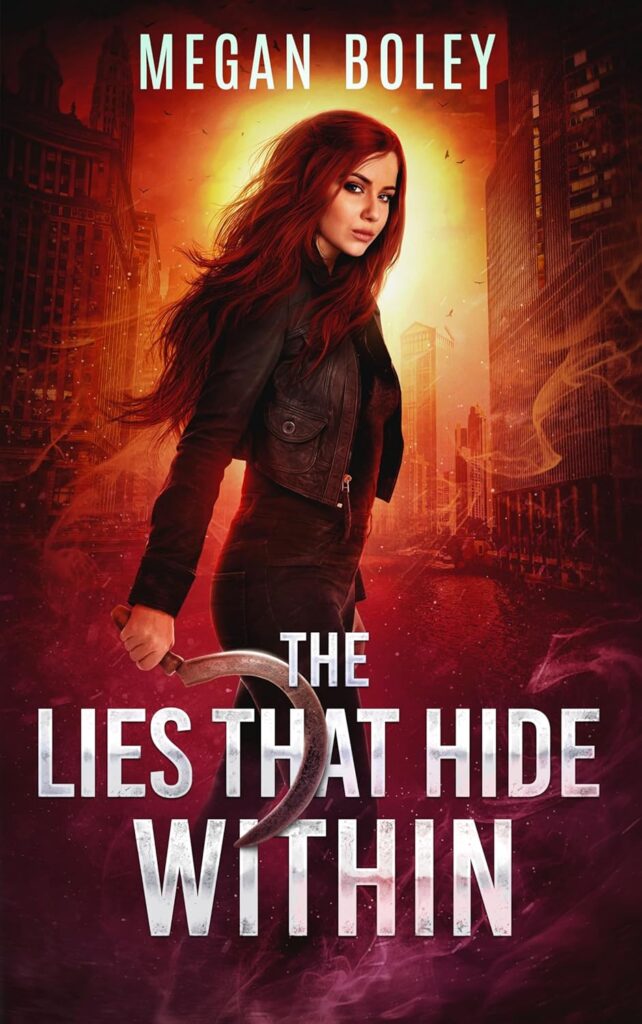

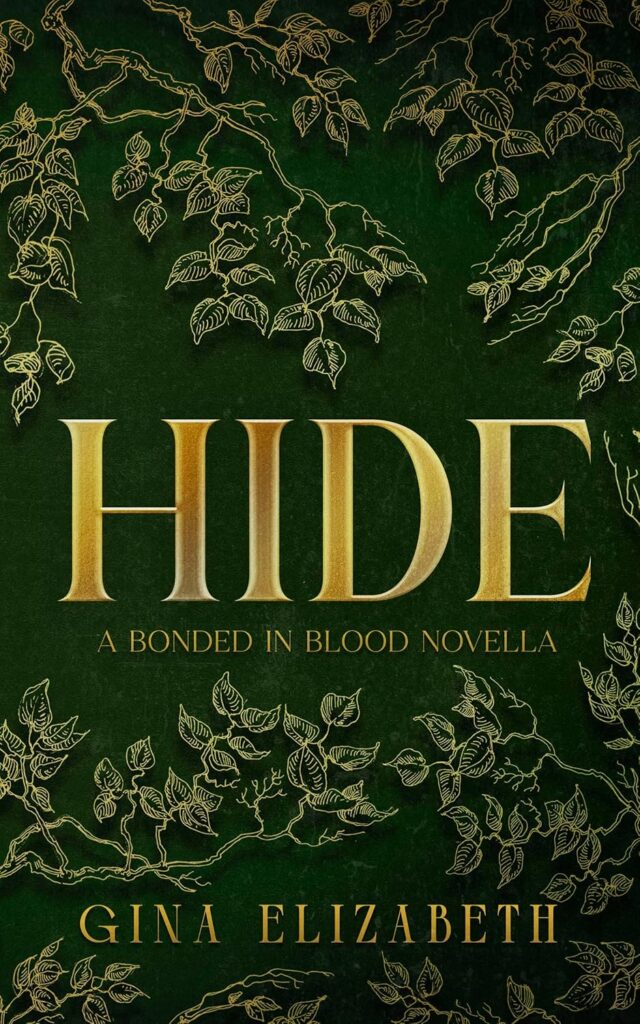

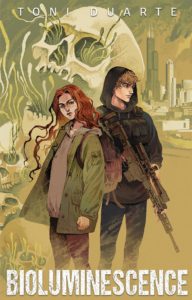

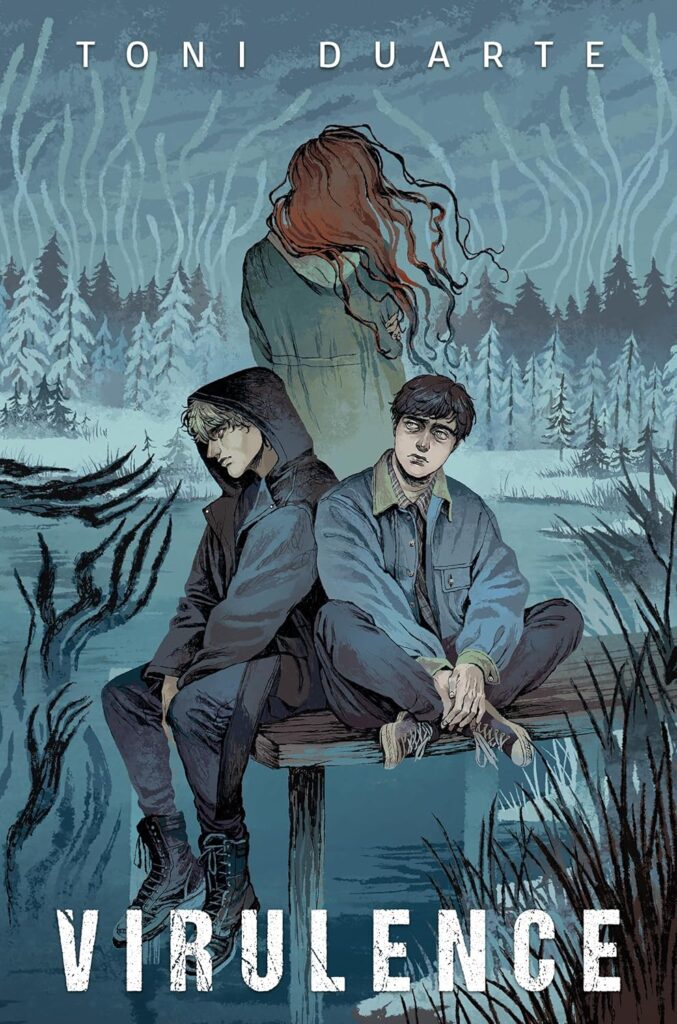

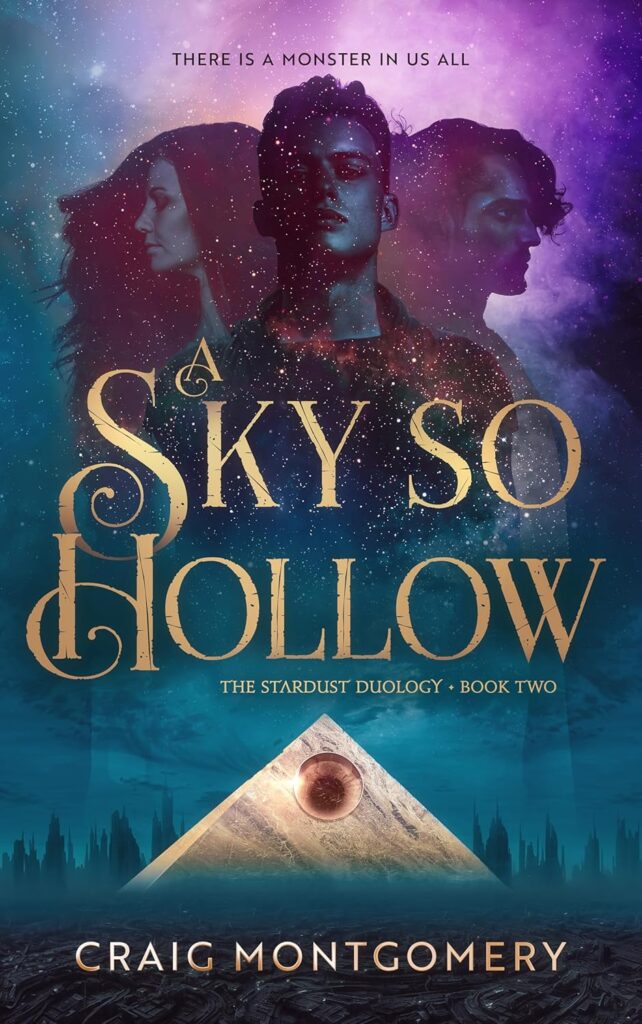

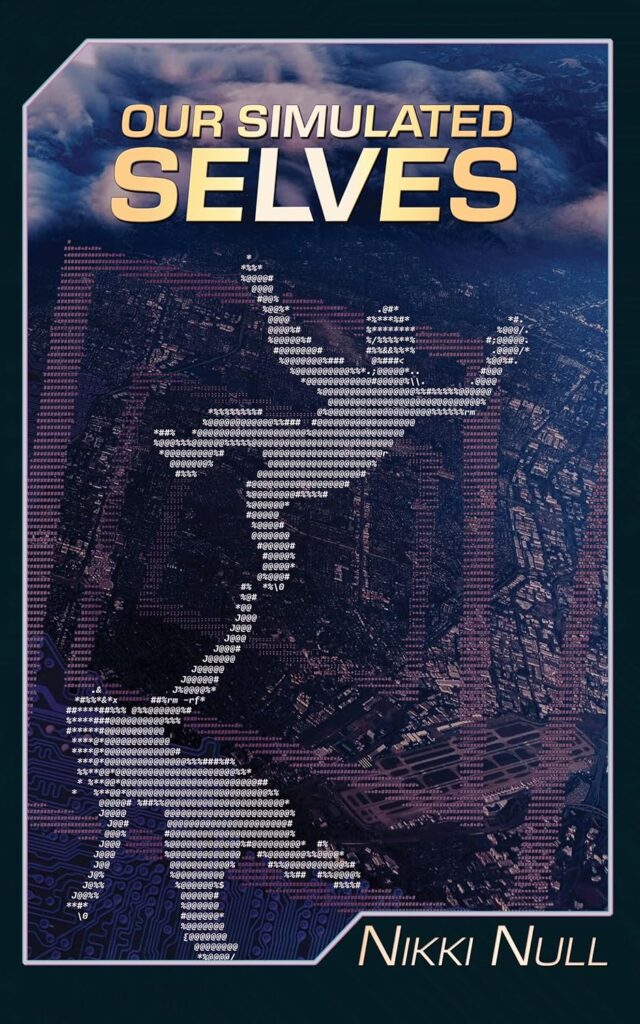

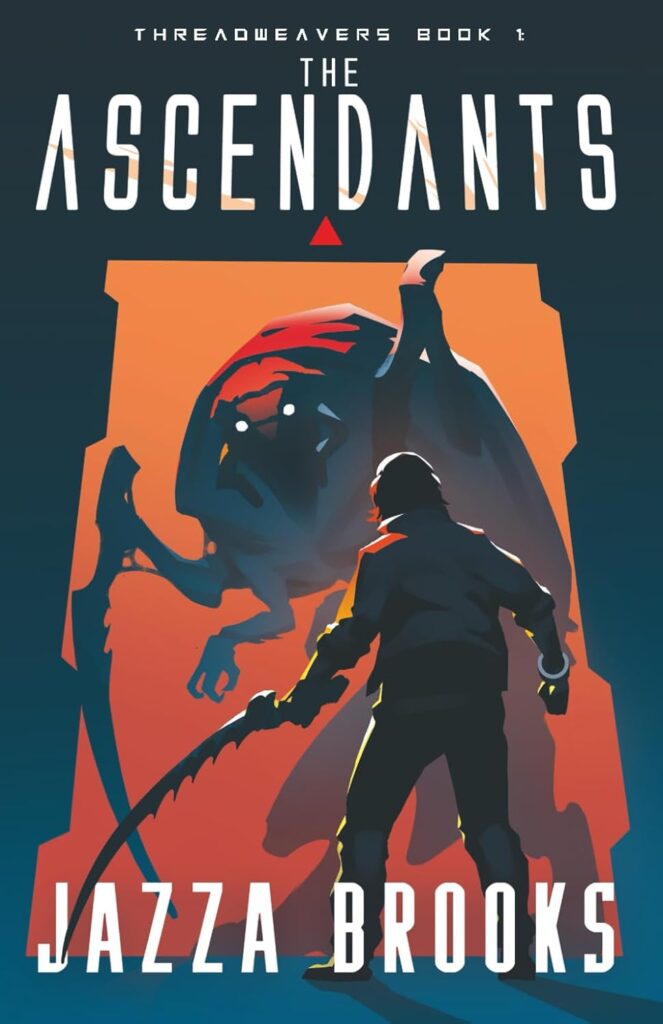

Want a look at some of the books I’ve recently worked on to gauge whether we’re a fit?