It’s time for a deep dive on dialogue tags.

I’ve written about the “said-is-dead” debate in a previous post, but decided to come back with further clarity on different methods of attribution and when/why an author might choose one over the other. This is short and sweet, so strap in and let’s get moving.

Dialogue attribution has three jobs:

As I see it, there are three considerations to keep in mind when we’re deciding how to attribute (or, tag) dialogue: clarity, delivery, and rhythm. In other words, we’re concerned with:

- Who’s speaking

- How the line is said

- How the line looks and feels as the reader encounters it

The primary purpose of a simple dialogue tag is clarity, or, identifying the speaker. For this, said is most assuredly not dead; standard tags like ‘said,’ ‘asked,’ and ‘replied’ are most affective. They’re inobtrusive and so well-worn that, when used correctly, they often disappear into the fabric of the narrative.

That said (heh), although attribution is the primary purpose of a dialogue tag, it can help to have more information about delivery. This is where said-bookisms come in. Alternatives to said/asked/replied can also be a useful part of a writer’s toolbox, so long as they’re used in moderation and truly are the right fit for the job.

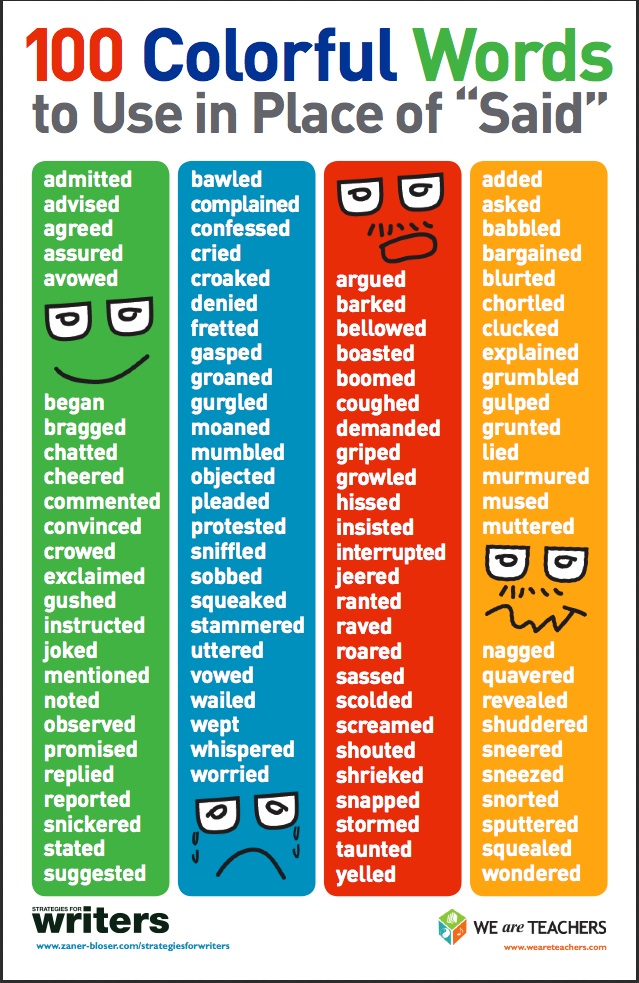

When I say ‘right fit,’ I mean they ought to be the simplest and clearest way of describing the line’s delivery. For example, common alternatives like shouted, whispered, snapped, and muttered are often appropriate in certain contexts. But beware! Said-bookisms are shiny, tempting words. Not only do they lend themselves to overuse, but they can become crutches for our writing when we use them as shortcuts for information delivery.

Snapped isn’t always the best way to convey a character’s irritation, but it’s a much easier way to convey that irritation than using narrative description, internalization, or context clues. Hence why sound-bite writing advice on social media tells new writers to stay away from said-bookisms; they can encourage bad writing habits if we’re not being very careful.

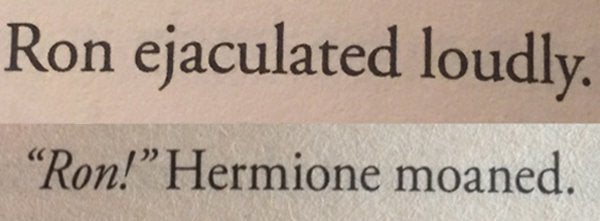

Another reason said-bookisms get dunked on with some frequency is because many of them are absolutely bananas, and should rarely (if ever) be used: ejaculated, espoused, pontificated… you get the picture.

(While there’s a time and a place for every kind of word, over-the-top tags make the reader feel like they’ve been punched in the jaw by the prose, and we really don’t want to do that by accident.)

The reverse argument, of course, is that “he said/she said” gets boring and repetitive.

And yes, it can…

…if the third consideration, “rhythm,” falls by the wayside.

In my mind, simple tags like he/she said should only make up a fraction of dialogue attribution. An overreliance on any one method will always cause problems, and said/asked/replied aren’t exempt from that rule!

So how do we add variety into our writing? By using the four following techniques:

Simple attribution

Simple attribution uses the said-asked-reply tags and/or leaves dialogue untagged because character voice is strong enough for attribution to be implied. This method works best when the reader is already aware of context and, rhythmically, we want to pick up the pacing. No space for excess words!

Assuming the reader already knows the characters, the setting, and what the conversation is (largely) about, we could have a quick exchange that looks like this:

“Time to go,” she said.

“I’ll be ready in a minute.”

If we have enough context for this to be intelligible, it could be a strong choice! It’s simple, it’s clean, and it reads fast. But if not, the reader won’t be able to figure who the second speaker is. In that case, more context might be necessary—but a said-bookism might not be the right choice, either, unless it provides that context!

When would a said-bookism be an appropriate choice?

Said-bookisms

Let’s say the ‘she,’ in this case, is a mother speaking to her son. She’s standing in the hallway and addressing him through a closed door. If the story is told from the son’s perspective, we won’t have any body language cues to gauge the mother’s emotional state and decipher how she delivers her line. One way to address delivery would be to use an appropriate said-bookism.

“It’s time to go,” she snapped. “Didn’t you hear me? I said your name four times.”

“Just a minute,” he said, scrambling for his backpack.

‘Snapped’ works, here, because it adds context. Notice, however, that the son’s line returns to a simple attribution tag—said—in order to balance the punch brought by the intensity of ‘snapped.’

Action tags

But that’s not all! We can also attribute dialogue through action, which, if the door were open, could provide enough framing context to eliminate the need for standard tags altogether. For example:

His mother peeked through the door. “Time to go, honey.”

“I’ll be ready in a minute,” he said, and set down his controller.

The mother’s action tag, along with the addition of the pet-name ‘honey,’, makes the identity of the speaker clear in each line, and does a lot more (albeit different) characterization work than ‘said’ or ‘snapped’ could, and gives us a nuanced picture of the mother’s tone and demeanor.

Attribution through internalization

Finally, we have attribution through internalization. This can be a bit weedy or difficult to wrangle when it comes to clarity, but when done well, it’s a powerful way of bringing the reader deeply into the POV character’s head. If you’ve ever gotten feedback that your writing lacks interiority, this type of attribution can really help to elevate your prose.

An example:

“Time to go!”

Ugh. His mother was the worst, always interrupting the middle of his game. They didn’t need to leave for another fifteen minutes, but she had a thing about being early in order to be on-time.

Fine—she’d have it her way, as always.

“I’ll be ready in a minute.”

In this case, the combination of context and internal narrative lets the reader know who’s speaking. The son unpacks the context for the reader, and this explanation makes it possible for the reader to get their bearings and fill in the blanks.

Said isn’t dead, but it’s not the be-all-end-all of attribution

These four tools will allow you to focus on what’s most important in a given dialogue exchange. Is it clarity? Is it pacing? Is it the lyrical nature of the prose? Is it the way the line is delivered? External action? Interiority?

Switching between these methods depending on circumstance will add variety and interest to your prose. They’re tools which can draw the reader’s attention to the aspect of the conversation that’s most important—a kind of authorial sleight-of-hand that works wonders in long or thorny passages.

Most importantly, however, mastering the full range of attribution techniques will cut down on repetitive usage of ‘said,’ which will in turn prevent you from feeling the need to rely on some of the (ahem) more creative said-bookisms out there.

Just…

Don’t be like JKR.